Hazardous work environments and inaccessibility to vaccines make essential migrant agricultural workers one of the highest at-risk groups.

By Gianna Gronowski

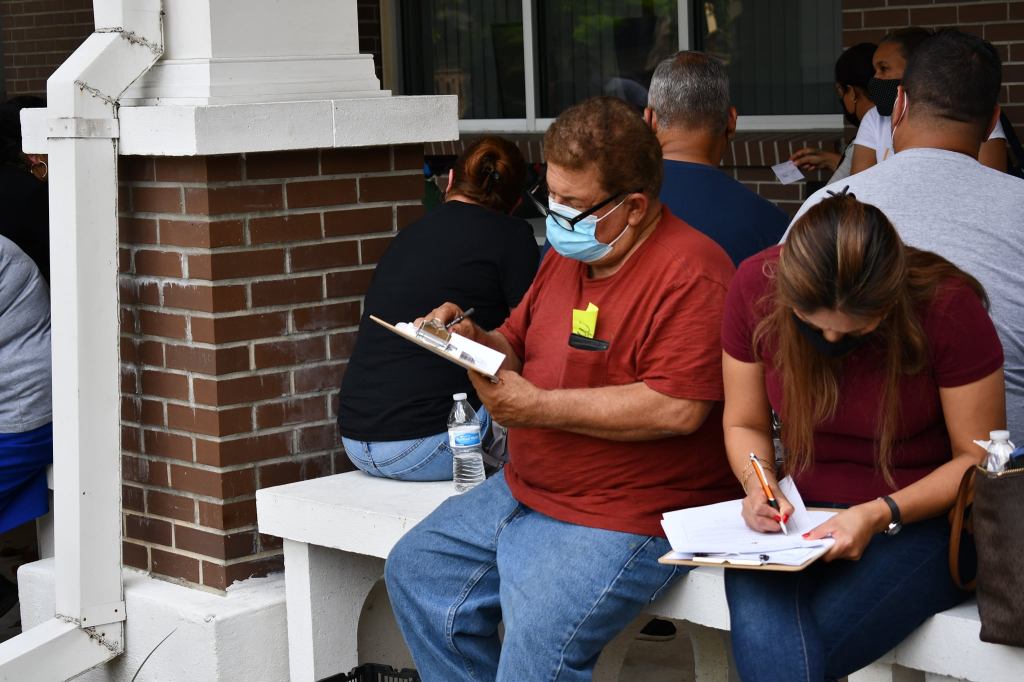

Essential migrant agricultural workers continue to labor in hazardous work environments with limited vaccine access, despite increasingly high infection rates.

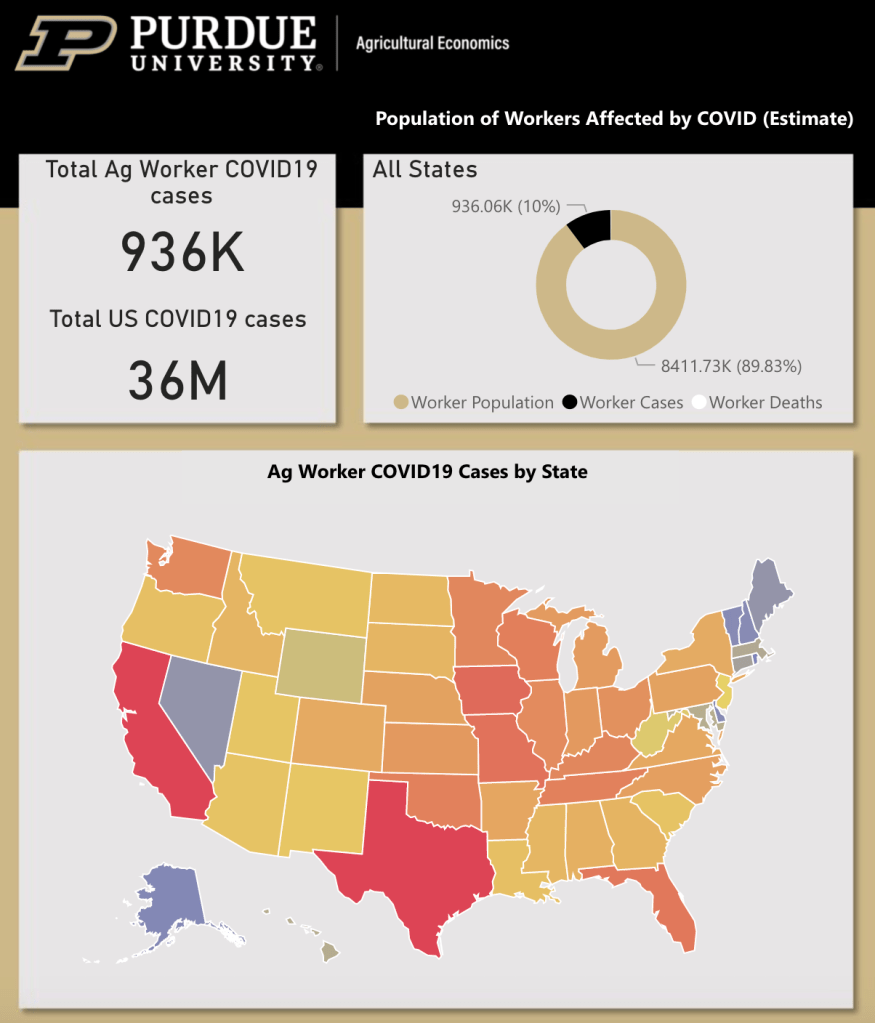

A study by Purdue University reported that at least 936,000 agricultural workers have tested positive for COVID-19 as recent as August 2021. The total is likely an underestimation due to undocumented and migrant workers not having access to healthcare resources.

Migrant agricultural workers are those that cross state and even national borders to follow the growing seasons of produce. The nomadic lifestyle and immigration status of these workers makes accessibility to healthcare services difficult.

Lideres Campesinas reported that many farms have ignored social distancing advice and continue to allow groups of up to 60 farmworkers working in close proximity. The farmworker and women led advocacy group sent multiple letters to Governor Gavin Newsom (D-CA) in attempts to gain safe working conditions for agricultural workers.

Contact tracing, COVID-19 testing, and quarantine practices were generally unheard of among agricultural workers in the fields.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) was scarce, with workers receiving “one mask for the whole week, and…the mask gets dripping wet, dirty, and ineffective in the first hour they’re outside,” according to Farmworker Association of Florida (FWAF) advocate Jeannie Economos. “Growers are more interested in getting their product out than they are in their workers’ health, safety, and wellbeing.”

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) did not provide clear guidelines on safe working conditions throughout the duration of the pandemic. The lack of a standard allowed for many workplaces to determine for themselves what safety measures qualified as adequate.

Such high infection rates should put agricultural workers in a prioritized demographic to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, but that is not the case for many of these workers.

The CDC initially issued recommendations for deemed essential food and agricultural workers to be eligible as part of the 1b tier for vaccinations. Yet each state ended up being responsible for its own vaccine prioritizations.

Republican Florida Governor Ron DeSantis decreed that proof of Florida residence must be verified in order to be eligible for receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. The requirement put in place effectively excluded those at the highest risk.

Advocacy group Farmworker Justice estimated a majority of undocumented immigrants comprises three-quarters of all U.S. agricultural workers. The State Department issued almost 215,000 H-2A temporary status visas to foreign workers last year.

Agricultural workers with temporary or undocumented status were largely unable to receive the vaccine in places that required government-issued identification, whether because they simply did not have the necessary documents on hand, or because they feared deportation.

Language differences proved to be additional barriers for immigrant workers to get accurate information on the facts regarding the vaccine or where to receive it. For example, many women did not know they could receive the vaccine if they were pregnant.

Immigrant advocacy groups wrote an open letter to Governor DeSantis requesting the prioritization of farmworkers in receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, but went largely ignored.

Farmworker advocacy groups like FWAF and the Guatemala-Maya Center took matters into their own hands and partnered with Florida Community Health Centers to administer vaccines to agricultural workers regardless of their immigration status. FWAF used membership cards to their organization as proof of identity.

The CDC recently announced recommendations for Pfizer vaccine booster shots for adults who are at increased risk of infection due to high transmission rates in their occupation.

Advocates hope for a federally mandated prioritization of food chain workers to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. Slowing the infection rate amongst a group of migratory at-risk workers could prove significant to decreasing overall COVID-19 transmission.

Leave a comment